Making attendance everyone’s business: What can we learn from local authorities about addressing school attendance

Issues with school attendance are not new. Shortly after the first piece of legislation to deal with the provision of education in England and Wales came into force in 1870, school attendance was made compulsory for those aged 5-10 (Education Act 1880) mainly due to challenges around truancy. Since then, attendance issues have been common features of our education system, particularly for those families from lower income groups.

In the Victorian era, this was due to parents not being able to afford to lose the income generated from their children working in factories. Today, a complex range of cultural, societal and structural barriers are holding our most disadvantaged children back. The legal sanctions in 1880, including fines and attendance orders, remarkably remain the same key legal levers for local authorities (LAs) today.

What is happening nationally?

The pandemic further disrupted the education of a generation of children, who spent more than one term out of school – about 61 days on average between March 2020 and April 2021. Five years on and nationally, the percentage of children attending has yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels and the full ramifications of this period out of school have not been completely quantified yet.

This has had a devastating impact on all children’s education but particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds. For instance, pupil absence has been identified as a sole driver of the widening of the disadvantage gap over recent years. The growth in the disadvantage gap at age 16 by 0.5 months (to 18.6 months) since 2019 is entirely explained by higher levels of absence for disadvantaged pupils (Education Policy Institute, 2025).

Chart taken from the Education Policy Institute’s 2025 annual report.

The impact of missing school runs far deeper than attainment, however. We have heard from many local authority colleagues, health leaders and school leaders that low attendance (particularly severe and persistent absence) has severely impacted on the health, mental health and wellbeing of children and young people, particularly those of secondary and college age.

A GP friend recently shared that they are seeing children who are not attending school due to anxiety and emotionally based school avoidance (EBSA) spending up to 14 hours per day on social media – essentially the entire time they are awake – creating a vicious circle of anxiety and declining mental health.

At primary level, school leaders have told us about the developmental delays, particularly around speech and language, that seem to have exponentially increased for those children who were socially isolated in their most formative years during the pandemic.

It is no surprise therefore that attendance is a priority for the Secretary of State, Bridget Phillipson, and the Department for Education, with programmes in place to further support families, local authorities and schools. Universal breakfast clubs, granular attendance data sharing between the DfE, schools and the LA, updated attendance guidance, attendance and behaviour hubs and attendance conferences/seminars are all welcome interventions. These have been accompanied by some green shoots of recovery: nationally, both overall attendance and persistent absence (missing over 10% of school or more) has improved year-on-year since 2021.

Yet, one in five children are still persistently absent from school. This has increased from one in ten a decade ago. Alongside severe absentees (those present in school less than 50% of the time), it is this cohort of children that schools and local authorities are increasingly worrying about the most. These are often our most vulnerable: our children living in poverty, our looked after children, our excluded children, our children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) who stand to benefit the most from attending school every day.

In order to understand the challenges, opportunities and effective approaches to addressing persistent and severe absence, we have spent time speaking to a range of local authority colleagues across the country with specific responsibilities for attendance.

What challenges do LAs face?

LAs carry the statutory responsibility to ensure that every child receives a suitable education, yet their capacity to do so is often hampered by systemic and contextual pressures. Across our discussions with LA leaders, several recurring challenges emerge.

First, there are complex underlying needs. EBSA, anxiety, and mental health concerns are increasingly cited as major factors behind persistent absence and severe absence. These needs often overlap with SEND, making it difficult to identify children early and to create clear, supported pathways back into education.

Second, many LAs describe a shortfall in wrap-around services. While schools are expected to tackle absence, the reality is that many children and families need sustained input from social care, health, and youth services. With these services under pressure, schools and LAs are left filling the gaps, often without the resources to do so effectively.

Third, there are wider parental and societal factors behind increased levels of school absence. The pandemic has shifted the ‘social contract’ between schools and families (although recent data suggests that parent/carer confidence in schools is returning). Some parents are now more willing to accept fines for term-time holidays, or to keep children home for relatively minor illnesses. Coupled with the cost-of-living crisis — which has put spend on uniforms, travel, and meals beyond the reach of some families — these attitudinal and behavioural shifts have eroded daily school attendance as a non-negotiable norm.

Finally, there are operational constraints. Despite national efforts to improve data sharing, some authorities would prefer the analytical capacity to make full use of the data they receive from DfE. The result is that vulnerable children risk slipping through the cracks. As one LA colleague told us, “there are 13- and 14-year-old lads on estates who don’t even know which school they are registered at.”

Graphic showing the approaches of four LAs to strengthening attendance.

What does good practice in supporting attendance look like?

Despite these challenges, we have observed promising practice across the country. Not many local authorities have cracked the issue, but councils doing well tend to combine strategic clarity with inclusive, child-centred practice.

In places like Surrey, consistent local messaging frames schools as protective spaces for wellbeing, embedding attendance in a narrative of safety and care. Hackney has invested in trauma-informed staffing, treating attendance as a marker of wellbeing and ensuring that interventions support the whole child. North Tyne takes a data-driven approach, reviewing every child with under 50% attendance through monthly multi-agency panels, ensuring no child is overlooked.

Across Greater Manchester, authorities such as Tameside have embedded multi-agency working, bringing in health, social care and police colleagues to pledge their support and actions they will take to support school attendance. Stockport, meanwhile, has rolled out a consistent local communications campaign — “Attendance matters: every day counts” — to reinforce the message with families and schools. In Rochdale, taking a child-centred approach through consistent forensic work with a handful of severely absent children and their families is starting to reap dividends through improved attendance for the most vulnerable pupils.

Good practice also means tailoring responses to particular cohorts. Traveller families, children in care, those with SEND and/or EBSA, and children facing poverty all need differentiated support. Some LAs are developing EBSA toolkits, others are experimenting with predictive analysis to spot children at risk of future absence based on current patterns.

Finally, good practice is relational and preventative. Attendance is everyone’s business, requiring trust between schools, LAs, and families. Initiatives such as the School Attendance Liaison Practitioner Pilot in East Sussex show how new roles can bridge home and school, making daily contact with families, supporting face-to-face meetings, and reinforcing positive routines.

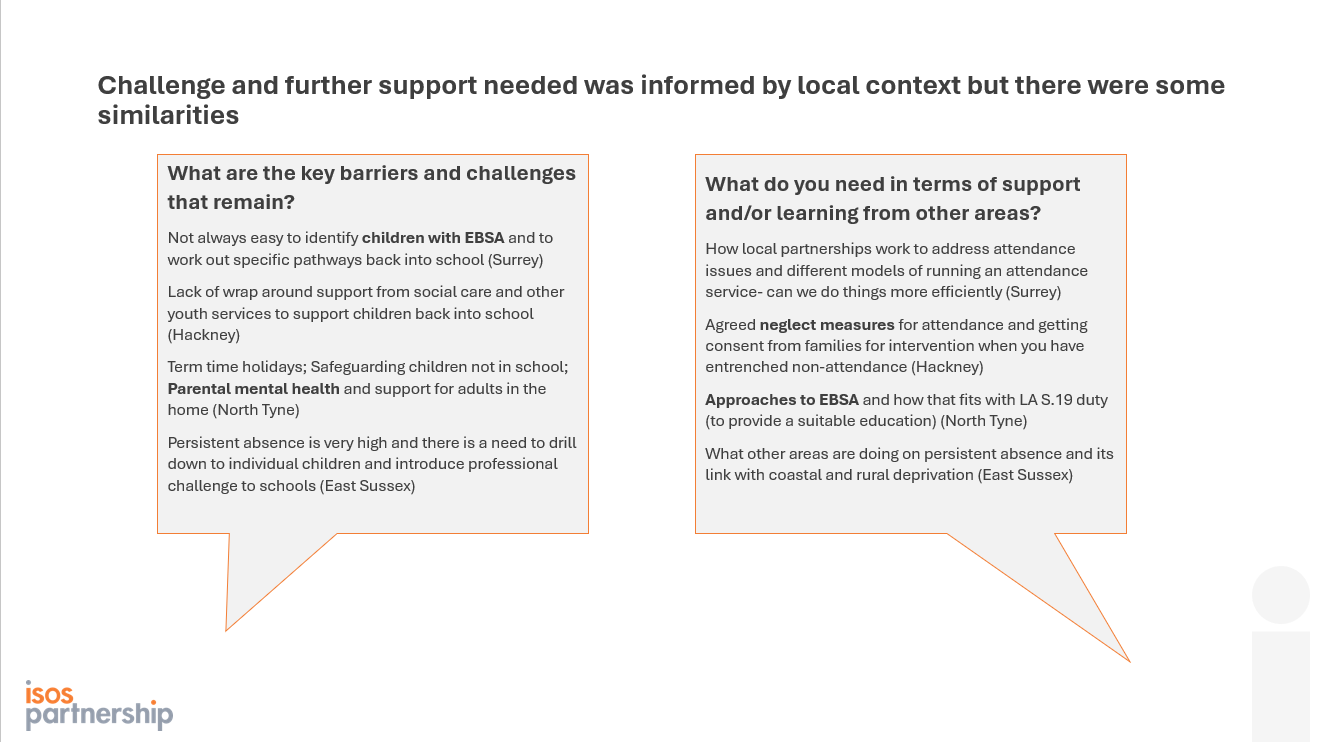

Graphic showing the key challenges and areas where further support would be useful described to us by the LAs with which we worked.

How can Isos Partnership help?

Our work across multiple contexts — from national pilots to local deep dives — has given us both breadth and depth of insight, making us well placed to help local authorities navigate this landscape. We have developed two packages of support, which can be tailored and combined to suit local needs.

#1. A granular approach to vulnerable cohorts

Through our work with local authorities and Combined Authorities, we have developed a ‘granular approach’ to working with vulnerable cohorts. This involves focusing in on individual children with vulnerabilities (often using absence as an indicator), forming an in-depth understanding of the wide range of barriers they might be facing, and designing tailored support to help overcome them.

We can facilitate local teams to develop a granular approach to addressing the attendance of their most vulnerable learners, working through the following steps:

Curiosity – identify a theme or cohort via data analysis or discussion with settings and practitioners;

Case studies – identify a small number of individual young people to focus on;

Dialogue – agree a model of practice for the case studies, based on empathetic listening and person-centred action planning;

Action plan – build a plan of action grounded in practical, achievable steps. Be prepared for this to be ongoing rather than a short-term, time-limited intervention;

Capture the learning and embed – within services, schools and settings, and wider strategies.

#2. Review of local authority systems and processes

LAs that have strong systems and processes in place are in a better position to address local attendance challenges. Implementing the expectations set out in the DfE’s attendance guidance (Working together to improve school attendance - GOV.UK) are a good starting point, but our work with LAs has highlighted how they are going further to support an improving attendance picture.

We can support LAs through a review of their current systems and processes, including:

analysis – of local attendance, persistent absence and severe absence data (both publicly available and held by the LA) to highlight trends over time, comparing with other LAs, between neighbourhoods within your LA, and between specific cohorts in order to develop specific attendance themes and lines of enquiry to inform next steps;

internal review – of current LA attendance systems and processes through a series of key internal interviews/workshops with strategic and operational leads and an analysis of LA attendance structures and policies;

engagement with schools – based on interviews with school and MAT leaders to determine attendance priorities, strengths and barriers in relation to working with the LA;

multi-agency engagement – engaging with stakeholders across health, social care and the police to determine and understand current engagement levels with the attendance agenda; and

summary – of findings, including recommendations for improving LA attendance systems and processes, and a plan for implementing change.

We are keen to hear from and support LAs, Combined Authorities and local partnerships on how they are addressing their own attendance challenges. Please do get in touch (adam.lewis@isospartnership.com) if would like to talk to us about how we can help.