How local education systems are responding to the coronavirus crisis: Part 1

‘This has probably been the hardest period of my professional life.’

These were the words of a former secondary school leader, now in a local authority (LA) leadership role, about the period between the partial closure of schools, settings and colleges in England after Friday 20 March and the end of the spring term 2020. The period of the coronavirus crisis and the measures that have been adopted to deal with it are often referred to as ‘unprecedented’. Until a matter of weeks ago, it was scarcely imaginable that education settings in England would be closed to all but a small group of children, while families across the country would be told that they must stay at home unless venturing out for a small number of permitted reasons.

Managing the transition to these new arrangements has been an enormous undertaking, particularly within local education systems. As this situation unfolded, we thought there would be value in –

capturing how local areas were responding to the challenges posed by the coronavirus crisis;

gathering reflections about what had and had not worked during the initial period following the partial closure of England’s schools and other educational settings; and

understanding how leaders within local education systems were adapting to the “new normal” and planning for a “return and recovery” phase.

In particular, we wanted to see if there were common experiences, learning and practical tips that might usefully be shared across local areas as they grapple with the implications of the crisis. To do that, during the two weeks of the Easter holidays, we spoke to LA leaders in 10 local education systems, as well as those working in leadership roles across local areas, to gather their reflections on the period following the announcement of the partial closure of England’s schools and their thoughts on the next phases of the response to the crisis. This blog summarises the key messages drawn from those conversations.

Part 1: Reflections on the pre-Easter period

In the final two weeks of the spring term, local education systems were focused on two main sets of operational priorities.

In our 2012 report on the then changing role of LAs in local education systems, we described a role that focused on three core responsibilities –

ensuring a sufficient supply of places in schools and settings;

supporting vulnerable children; and

ensuring high standards in education.

During the period where the majority of children are not attending schools or settings, local education systems have focused on two main sets of operational priorities. These correspond to two of the three roles we described in our 2012 research.

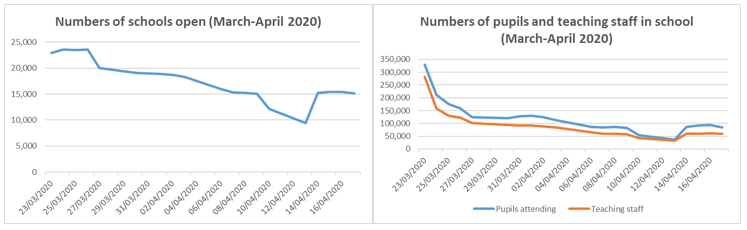

First, local education systems have had to reorganise the offer from local schools and settings to move within a matter of days to a situation where the majority of children will not be attending. LA leaders described a picture in which the majority of schools had remained open in some form, but with the number of pupils attending and staff in school decreasing in the final weeks of term and over the Easter holidays. This is reflected in data published by the Department for Education (DfE), which show that –

the proportion of schools open on 23 March, the first day after the partial closure announcement, was 93%, falling to 78% a week later (30 March), and remaining between 61% and 64% during the Easter holidays (not including the Easter bank holiday weekend, when the proportion was lower); and

the proportion of pupils attending schools dropped from 3.7% on 23 March to 1.3% on 30 March, and remaining at 0.9% during the Easter holidays (likewise, not including the Easter bank holiday weekend).

A key task for leaders of local education systems has been liaising with schools on a daily (and sometimes more frequent basis) to understand which schools are open, which pupils are attending, and how schools are coping with staffing shortages, as well as communicating plans for implementing the latest guidance documents from the DfE. The data presented by the DfE reflects the processes that leaders of local education systems have set up to maintain real-time information about what is happening in schools during the crisis.

While some schools have consolidated their offer and are delivering from a single “hub” – schools in the same trust or those operating in the same geographical area, with individual schools providing staff but delivering from a single site – the view from local areas was that there were barriers to schools operating in this way. These included issues around vulnerable children being educated by unfamiliar adults in unfamiliar settings, and around vetting checks. This picture of a large proportion of schools remaining open, albeit with fewer pupils and staff, chimes with what the data published by the DfE suggest.

With the majority of children not attending schools or settings, the second operational priority of local education systems has been one of ensuring, in the words of one Director of Children’s Services, that there are “eyes on” vulnerable children. This means putting in place arrangements to check on the wellbeing of children who are known to be vulnerable to risk, and who ordinarily would be seen by school staff and other professionals daily so that any signs of harm would be picked up and acted on. The description of these as two key priorities during this period was consistent across all of the local leaders to whom we spoke. These twin priorities have meant that local education systems have needed to develop a new “operating model” for responding to the crisis. This has involved –

setting up new structures for liaising with schools and settings – for example, each school and setting having a nominated liaison or point-of-contact, either drawing on existing structures or matching officers to schools and settings within a local “patch”;

maintaining regular communications with schools and settings – through daily emails, ensuring all messages to schools and settings go through a single point-of-contact (e.g. a senior education leader within the LA) and virtual school leader meetings, so as to ensure a swift and regular flow of information (local leaders emphasised the scale of the task of interpreting and implementing the significant volume of guidance from central government), consistent communications and interpretation of national guidance, and rapid sharing of good practice; and

setting up processes for tracking vulnerable children – drawing together lists of children who are known to children’s services or potentially could be vulnerable during this period, undertaking risk assessments, and putting in place appropriate checks or arrangement to get children into school who need to be.

The process of setting up this new “operating model” has highlighted two important issues.

First, it has underscored the importance of the relationships between education and children’s services. Where there has been strong collaborative practices and information sharing previously, local areas have been able to move to this new mode of operating swiftly, and have developed robust processes for tracking potentially vulnerable children easily. In other local areas, however, the period following the partial closure of schools had revealed mismatches in information about potentially vulnerable children held by different services and schools, and a lack of understanding and established relationships between schools and settings, education and children’s services.

Second, it has exposed challenges in balancing the imperatives of promoting public health and protecting potentially vulnerable children. Local leaders described to us some of the challenges of balancing the message about the need for people to stay at home with that about which families can or should send their children to school (and whether the latter was an entitlement for families or an option to be considered by professionals). This issue has to come to the fore recently, with DfE data showing that around 5% of those children defined as vulnerable were attending schools, and 6% of those eligible were attending early years settings – an issue that has been highlighted in a recent report by the Office of the Children’s Commissioner. Local education system leaders described how they were taking a risk-based approach, developing overall lists of all pupils, collating information about those who would be potentially vulnerable, and identifying how professionals could be assured that those children were safe, either through checks or in some instances getting the children into school.

Relationships with schools and settings, and across services, has been crucial in this period, but the demands placed on local education systems have also highlighted the vital role played by local authorities.

As our 2012 report and research since has shown, the role of LAs within local education systems has been a live and topical issue over the last ten years. While quick to highlight the pro-activism, engagement and commitment of school, setting and college leaders, as well as the helpful regular lines of communication established to DfE through the Regional Schools Commissioners’ teams, the leaders of local education systems to whom we spoke all drew attention to the vital role played by LAs in co-ordinating and managing the education system’s response to this crisis. LA leaders also argued that the sort of granular, “hands-on”, operational tasks required of local education systems – staying in touch with schools and settings, checking on staff levels, co-ordinating checks for vulnerable children – illustrated the essential role of LAs in convening partners, communicating key messages and co-ordinating a local system’s response to the crisis.

While we heard examples of school-to-school partnerships helping schools to manage their offer and support staff wellbeing, we did not hear of examples of local strategic partnerships of school leaders playing a leading role in managing a system-wide response to the crisis: the latter role was being played by senior LA officers. Given the debates about the role of LAs in the English education system over the past decade, colleagues wanted to ensure this point was not lost once the immediate crisis recedes.

Part 2: Looking ahead

Local leaders are identifying similar sets of questions, both for the immediate phase of consolidation to the “new normal” …

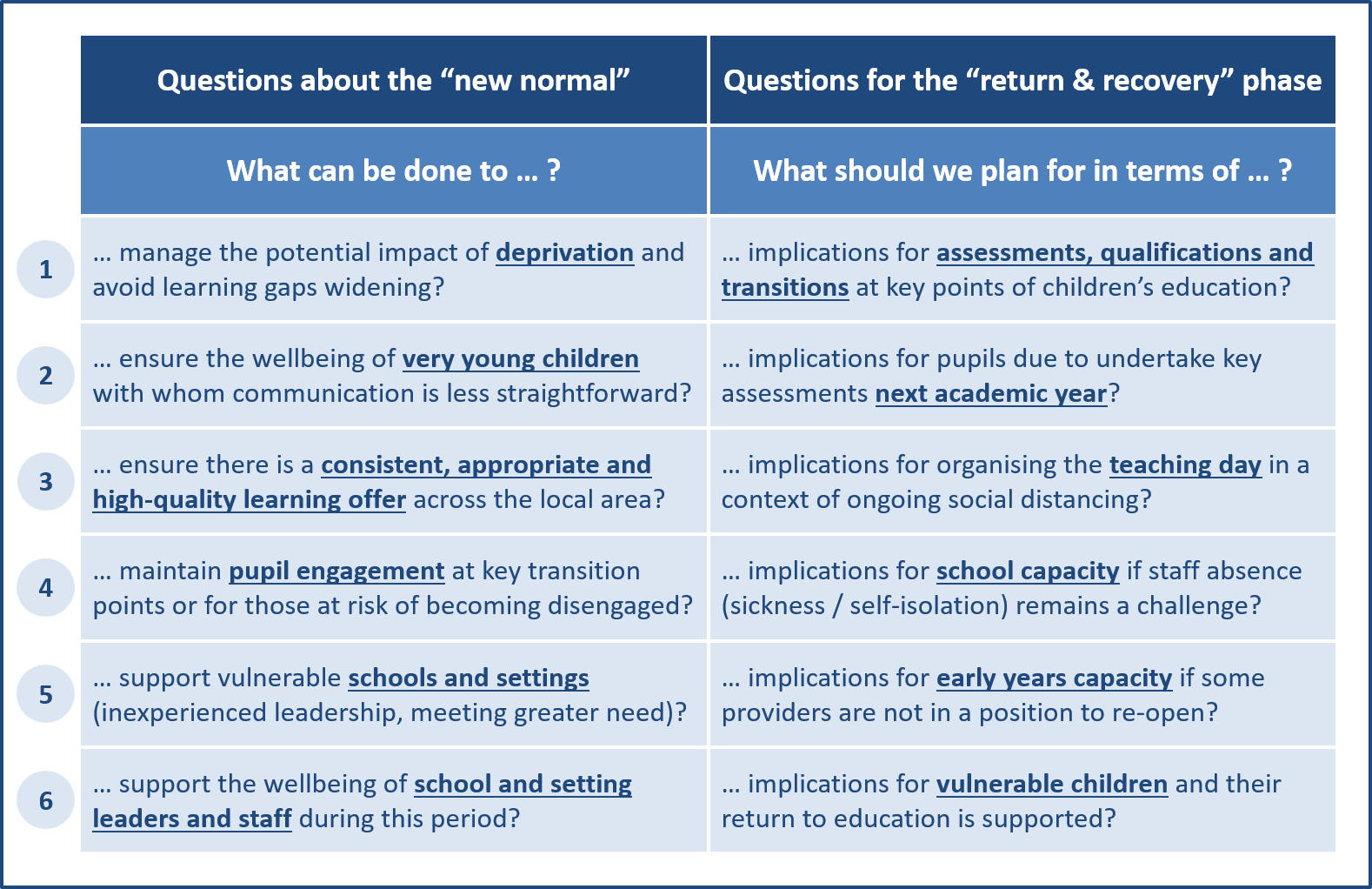

Since education settings were partially closed, leaders within local education systems have been identifying key questions about how local education systems adapt to a “new normal” where the majority of children are not in schools or settings, and about how the system prepares for a phase of “return and recovery”. At the time we spoke to them, leaders in local education systems were identifying and beginning to work through the implications of these key questions, but the immediate focus on the two operational priorities we described – the re-shaping of schools’ offers and keeping eyes on potentially vulnerable children – had meant that hitherto there had been limited time to formulate responses to these questions. It was significant, however, that leaders in very different local education systems identified similar sets of questions. This suggests that there may be value in supporting leaders from different local areas to reflect on these questions and share ideas together. These questions are summarised in the graphic below.

Six key questions local education systems are considering as we adapt to the “new normal”, and six more as we plan for the “return and recovery” phase

The first set of questions local leaders posed related to the third key role of LAs and local education systems – after place planning and supporting the vulnerable, promoting high standards in education. Specifically, local areas were grappling with questions about how best to support the education of pupils and the “health” of schools and settings, during a period when most children would not be in school. These questions included –

how to manage the potential impact of deprivation and avoid learning gaps widening, including for children living in poverty, without access to digital devices but more broadly the conditions that support learning;

how to ensure the wellbeing of all children, including very young children where it may be less straightforward to check on them;

how to ensure that there is a consistent, appropriate and high-quality offer of learning across the local education system, with parents given the appropriate help to support their children’s learning;

how to maintain pupil engagement, particularly for those who were at risk of becoming disengaged, those approaching transition points in their education, and those at risk of dropping out of education, employment or training (becoming NEET);

how to support more vulnerable schools and settings, including those with less experienced leadership and governance, to manage the crisis and come out of it in a healthy position in organisational, staffing and financial, as well as educational, terms, as well as more specialist settings with high proportions of vulnerable children, such as special schools and pupil referral units / alternative provision settings; and

how to support the wellbeing of school and setting leaders and staff during a period of extended strain on those staff.

… and for the “return and recovery” phase to come.

The second set of questions local education system leaders were asking themselves related to the return and recovery phase. Despite the uncertainty about when there may be a “return and recovery” phase, local leaders recognised that there would need to a plan for completing aspects of the 2019/20 academic year and for dealing with the implications of partial closure such that schools, settings and pupils could hit the ground running at the start of the new academic year. Some of the key implications highlighted by local leaders included –

implications for assessments, qualifications and transitions, particularly for children in the early years, those preparing to move to secondary school, those who would have been taking GCSE or A-level exams or other key qualifications this summer, as well as those at risk of dropping out of education, employment of training;

implications for pupils due to undertake key assessments next year, including children in Year 5, Year 10 and Year 12 who are part-way through their study programmes and will have missed a significant period of learning;

implications for how to organise the teaching day, staffing, and in-school/-setting activities in a context where social distancing measures remain in place;

implications for school capacity, with staff absence (due to sickness or self-isolation) having been challenging before partial closure and likely to continue to pose challenges to schools when pupils start returning;

implications for early years capacity, with 45% of settings estimated by the DfE to be closed (and the status of a further 30% not known), local leaders were concerned about whether there would be sufficient early years provision, and whether some early years providers will have had to close permanently, once the immediate crisis recedes;

implications for more vulnerable pupils, specifically how schools and settings prepare for the return of children who will have had very different experiences of learning during the lockdown, and where there are likely to be significant gaps in learning and support needed to help children reacclimatise back in their school or setting.

One LA leader talked about a “domino effect” as the various implications of coronavirus and the partial closure of schools and settings started to be tallied up.

While there is uncertainty about when the “return and recovery” phase might come, local education system leaders were clear that it will not simply be a case of going back to how things were before; careful and pro-active planning will be needed about how local education systems adapt to the after-effects of the crisis.

The final point local leaders emphasised was the need for measured, pro-active planning for how local education systems should operate as we come out of the lockdown. In light of the conclusions of the recent publication from the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, which suggested that re-opening schools could bring the transmission (reproduction rate) of covid-19 back towards the level of one or above, it is unlikely that local education systems will simply return to business-as-usual.

In much of our work around inclusion and special educational needs, for example, we often hear school leaders, LA officers and families highlighting some of the limitations imposed by the structure of the school day, curriculum and measures of effectiveness. If we are about to enter a period in which the way in which schools and settings operate, and how pupils are educated when they are there, will look very different, then this will present opportunities to rethink how the education system in England needs to work for all pupils. It is unlikely that this thinking can be driven solely by national government, and there will continue to be the need for dialogue within and across local education systems about how to adapt to and deal with the many implications of coronavirus on the education system.